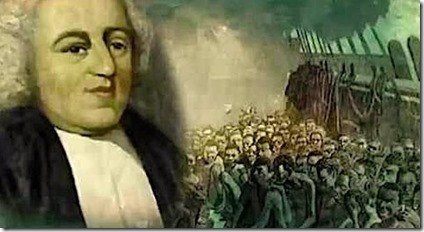

John Newton, an atheist and the captain of a slave-ship, is caught in a violent storm. He cries out to God for rescue. The ship is delivered and so is a young John Newton. Upon hitting the shores of England, Newton gives up his career as a slave-trader and becomes a preacher—laboring not only to proclaim the gospel but also the abominable slave-trade in which he was involved. Oh, and somewhere in there he also wrote a song called Amazing Grace about the whole thing.

John Newton, an atheist and the captain of a slave-ship, is caught in a violent storm. He cries out to God for rescue. The ship is delivered and so is a young John Newton. Upon hitting the shores of England, Newton gives up his career as a slave-trader and becomes a preacher—laboring not only to proclaim the gospel but also the abominable slave-trade in which he was involved. Oh, and somewhere in there he also wrote a song called Amazing Grace about the whole thing.

I think that’s how most people imagine the life of John Newton. But it was far from this. The storm on The Greyhound was in 1748. His slave-trading days didn’t end until 1754. His “conversion” helped him to be nicer to the slaves but he did not consider it to be an abominable practice. Newton, in his Authentic Narrative, doesn’t even list his participation in the slave trade on his list of grievous sins. As Hindmarsh notes, “participation in the cruelty of the slave trade did not yet seem even to trouble his conscience”. (58)

It was not until 1788 that Newton wrote out his Thoughts on the African Slave Trade. Some historians will unfairly place this as the first time he spoke out against the slave trade. While this might be true of his public stance he was heavily involved in the efforts of both William Wilberforce and Hannah More. But Newton was certainly not nearly as vocal about ending the Slave Trade as he was after 1788. That’s some forty years after his conversion experience.

What do we do with this historically? How can someone be convinced of an evangelical gospel and be completely blind to something such as slavery for forty years? How could he stay silent? How could it have been such a minor note in his narrative up until 1788?

A Few Proposals

One point to consider is that even though Newton considers 1748 the time of his conversion it would be another six years before he was influenced by evangelicals. His conversion at this point was mostly a change of morality, but he considered his conscience to still be stricken for quite a few years after his Greyhound experience.

Secondly, there was a vast difference between anti-slavery sentiment and abolitionist sentiments. Many in England thought that slavery was an ugly necessity. Many thought that abolition would have jolted the economy and the nation in such a way that it would have done more harm than good. The move from a slave captain, to an anti-slaver, to an abolitionist was a bit slow with Newton. A few dots had to be connected in his mind and heart.

Assessments such as that of Vivian Yenika-Agbaw are not as charitable to the actual persons involved:

“even in his plea for abolition of slave trade, he still placed a higher value on European lives, the perpetrators of the trade. It is only after he had made a case for their lives that he later described the condition of the slaves. This White supremacist legacy continues to affect race relationships even in contemporary times.”

It is correct that Newton’s Thoughts on the African Slave Trade began with the harm such a practice had upon the English people themselves. But this hardly makes Newton a white-supremacist. It makes him a faithful orator. He was appealing to the common humanity and showing how this was inconsistent with something as abominable as the slave-trade. Newton himself knew the arguments that it would take for one to move from being a slaver to a passive observer and then to take the appropriate step of being actively opposed—to become an abolitionist. So he appealed to their own self-interest first (reminded them of their humanity) and then moved to express the horrors of the treatment of Africans. If one reads the entire document you see that Newton labors to humanize the slaves. In fact he even goes so far as to suggest that their morals might even be superior to those who are slave-traders.

Why Did It Take So Long?

Newton himself said that his Thoughts were too late. He wished his eyes would have been opened and that he would have spoken sooner. But I think his journey, and as I’ll show in a moment, his own words help us to assess those who are caught up in these cultural moments and turn blind-eyes to atrocities. How do you categorize? Was John Newton unconverted until he joined the cause of abolition? Answering this question has implications for our day as well. (And I’ll attempt to flesh that out a bit more in the coming days).

For now, I’ll have you notice this. Consider these words from Newton in 1794:

I do not rank [the African slave-trade] among our national sins, because I hope, and believe, a very great majority of the nation earnestly long for its suppression. But, hitherto, petty and partial interests prevail against the voice of justice, humanity, and truth. This enormity, however, is not sufficiently laid to heart. If you are justly shocked by what you hear of the cruelties practised in France, you would, perhaps, be shocked much more, if you could fully conceive of the evils and miseries inseparable from this traffic, which I apprehend, not from hearsay, but from my own observation, are equal in atrocity, and, perhaps, superior in number, in the course of a single year, to any, or all the worst actions which have been known in France since the commencement of their revolution. There is a cry of blood against us; a cry accumulated by the accession of fresh victims, of thousands, of scores of thousands, I had almost said of hundreds of thousands, from year to year. (Works of Newton, Vol 5, p262-263)

Notice here that Newton does not call this a national sin because he believes the people are mostly ignorant and blinded to their sin. Their conscience has not yet been fully pricked. Other narratives are more compelling. “Petty and partial interests” are more prevailing upon their minds than “justice”. They are wrong. They are in error. But he’s not willing at this point to call it a national sin, because he doesn’t belief their actions are willful rebellion.

Now notice what he says in 1797:

Enough of this horrid scene. I fear the African trade is a national sin, for the enormities which accompany it are now generally known; and, though perhaps the greater part of the nation would be pleased if it were suppressed, yet, as it does not immediately affect their own interest, they are passive. (Newton, Vol. 5, p291)

Three years later Newton believed that “the enormities” were now generally known. People saw. People understood. They just did not care. This wasn’t merely ignorance or distraction, it was now willful rebellion. Their consciences had been ignored and then seared.

If we consider Newton’s own journey and his words here I think it can help us navigate some of the sticky questions that come up when assessing both history and current debates.

That’s why tomorrow I’m going to try to answer this question from the thoughts of Newton…

Can someone be a slave-holder and still a Christian?

—

Photo source: here