I have a filing system for anonymous letters that I receive. They typically go straight from my hand into the trash. If somebody cannot attach their name to a critique then it makes it almost impossible to deal with it biblically*. This is not to mention what such a letter does to someone like me with trauma history.

I have a filing system for anonymous letters that I receive. They typically go straight from my hand into the trash. If somebody cannot attach their name to a critique then it makes it almost impossible to deal with it biblically*. This is not to mention what such a letter does to someone like me with trauma history.

I treat anonymous criticism on the internet pretty similarly. There are reasons why somebody might need to remain anonymous so on occasion I’ll interact with someone on social media who has a crafty username instead of a real name. For the most part my principle is to not give weight to anonymity.

Is it possible, though, that in our polarized climate a bit of anonymity could be beneficial? Let me explain.

I’m a Fantasy Football expert. My record doesn’t agree with that assessment, but in my mind I’m the smartest one in every league I join. It’s just that dumb luck for others sometimes gets in the way of my success. Part of what makes me so smart is reading Matthew Berry.

Berry has this fun little exercise he enjoys doing. Here is an example:

Player A: 21.9 PPG, 68.6% completions, 265.1 pass yards per game, 2.1 TD passes per game

Player B: 22.0 PPG, 67.3% completions, 260.1 pass yards per game, 2.3 TD passes per game

You don’t know who these players are, but you look at these stats and you think, “I’d take either of these dudes.” And then he reveals that player A is actually Ryan Tannehill and player B is Patrick Mahomes from week 7 of 2019 to November of 2020.

I would have never taken Tannehill over Mahomes. (If you’re more familiar with movies than football let’s just say that Patrick Mahomes is Brad Pitt and Ryan Tannehill is Marty Feldman). Yet when Berry frames his argument with the anonymous player A and player B it puts away all my pre-conceived notions about these players. I only look at the facts. I have to consider what is being said.

When he reveals that Tannehill was player A and Mahomes was player B, I do still argue with his conclusion. I ask about rushing yards and rushing TDs. Are they scoring the same amount of fantasy points? Does injury or teams they played against factor into anything? But, and here is the clincher, I was less polarized than if Berry would have started with Tannehill vs. Mahomes.

Can Anonymity Disarm and Decrease Polarization?

In some ways what Berry is doing is similar to what the prophet Nathan did with David. He told a compelling story and left out a few key details. He disarmed David and the king was able to see the facts as they stood. When Nathan lowered the boom, “you are that man”, there wasn’t much of a way for David to weasel out of Nathan’s loving net.

Chris Bail, author of Breaking the Social Media Prism, argues for the value of an anonymous social media platform. I’m skeptical, but I do think there could be some value in this at the “think tank” level. Bail is behind an interesting idea called DiscussIt. After observing interactions on this platform for months, Bail was given hope that “anonymous forums might facilitate more productive conversations across racial lines.” (Bail, 126)

It’s an idea worth considering. I don’t believe anonymity is generally helpful—but I’m open to the suggestion that in the right setting anonymity may actually be beneficial for decreasing polarization.

What do you think?

—

I say typically because there might be reasons for someone to give an anonymous letter. And there may be valid critique and a reason why said person cannot attach their name. So in these instances I’ll perhaps give the letter to a trusted friend, have them read it, and tell me if there is anything I need to address.

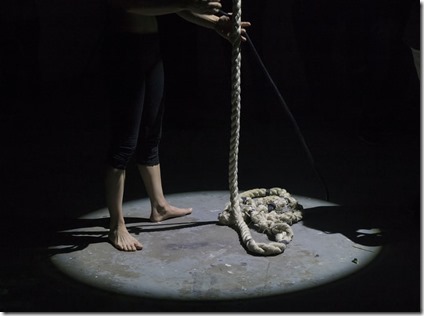

Photo source: here