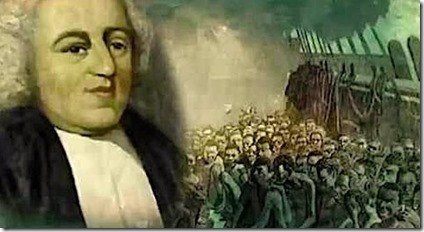

Yesterday, we looked at the slow-movement of John Newton from slave-trader to anti-slavery to abolitionist. It would certainly make me more comfortable to believe that once Newton became a believer that he immediately moved towards a position of abominating a practice so obviously erroneous as man-stealing. But he didn’t.

Yesterday, we looked at the slow-movement of John Newton from slave-trader to anti-slavery to abolitionist. It would certainly make me more comfortable to believe that once Newton became a believer that he immediately moved towards a position of abominating a practice so obviously erroneous as man-stealing. But he didn’t.

I would also note that I’m not incredibly comfortable with how long it has taken me to reject certain falsehoods or to embrace particular glories. Sanctification seems to always be a bit slower than we would prefer. But this slowness (or even at times absence) of sanctification in some areas causes us no little consternation when assessing our heroes (or villains) of the past.

Could a Christian be a slave-trader or a slave-holder?

That is a pressing question in our day as we look back upon the racism of our not so distant past. It has implications for our handling of monuments, naming of buildings, and a host of other issues. Today I want to engage this question through the lens of John Newton. How would he answer this question?

You will note that this question is not whether or not slave-trading (or holding) is consistent with Christian redemption? This question is really asking whether or not one professing belief in Jesus can hold a theological position or engage in activity which is inconsistent with Christian redemption.

I should also say from the very beginning that I doubt Newton would even answer a question framed this way. He’d likely say, “Let’s let the Lord decide”. He would probably prefer a question like, “What do we say of a person professing Jesus but living or believing in a way contrary to the faith?”

The Role of the Conscience

To such a question I believe that Newton would ask, “does he know that it’s wrong?” The conscience played a mighty role in the way Newton thought about the Christian life and making decisions. He believed that “Christ alone is the Lord of the conscience” (Vol. 6, 229) and that Christianity erred greatly when “by a fierce and rancorous superstition” the Church began to tyrannize “over the conscience, liberties, and the lives of men.” As Newton would write to a friend:

The experience of past years has taught me to distinguish between ignorance and disobedience. The Lord is gracious to the weakness of his people; many involuntary mistakes will not interrupt their communion with him; he pities their infirmity, and teaches them to do better. But if they dispute his known will, and act against the dictates of conscience, they will surely suffer for it. This will weaken their hands, and bring distress into their hearts. Wilful sin sadly perplexes and retards our progress. May the Lord keep us from it! It raises a dark cloud, and hides the Sun of Righteousness from our view; and till he is pleased freely to shine forth again, we can do nothing; and for this perhaps he will make us wait, and cry out often, “How long, O Lord! how long?” (Vol. 1, p. 316).

There is a difference between disputing the Lord’s known will and between ignorantly living in sin. Even though I believe his assessment was not wholly accurate this is why he was able to say in 1794 that the slave-trade was not a national sin. He believed they were living in ignorance. But by 1797 he was convinced that they were willfully going against their conscience.

Back to our question of slave-trading or slave-holding. This is why I believe Newton’s first question would be, “does he know that it’s wrong”? What foundation is this person reasoning from?

It is different for a person to say, “I know that the Bible teaches that this is wrong but I’m going to do it anyway,” and saying, “I do not believe the Bible teaches this is wrong”. The action itself may still be sin but one man is going against the “light of his conscience” and the other is not. There is a bit of a difference in how you engage such a person as well as how you assess the situation.

For both people, Newton would proceed to share the truth as he understood it in Jesus. But would ultimately leave that person up to the Lord’s care. He was very careful not to force notions into people’s hearts because, “notions resting in the head will only feed the flesh” (From Manna Horded).

What if they never repent?

What happens, though, if you continue to share the truth of Jesus with someone and they never come around to your understanding of the Bible? Or worse, what if they continue in something such as an abominable slave-trade. Should we then label them as unbelievers?

Newton was very skeptical of drawing lines. He was far more comfortable leaving folks to the Lord to decide. But it is interesting how he was able to move from not calling it a national sin in 1794 to then saying “I fear this is a national sin” in 1797.

Newton had far more patience and grace than most people. It is shocking to me that even in 1794 he could still think that people were mostly motivated by ignorance. That was six years after his Thoughts on the Slave Trade and the repeated efforts of William Wilberforce. I believe Newton had many conversations and this topic was on the forefront of discussion for those many years. Eventually Newton was able to come to the conclusion that people understood they just did not care. Here his view of the role of conscience would also come into play.

Preachers were adamant about preaching to the conscience in this period. They believed that this was a means that God used to convert sinners. But they also believed that repeatedly going against your conscience would leave you in a dire state. This is why as he pleaded with his adopted daughter to come to Christ he would encourage her to “attend to his voice in your conscience”. (Vol. 6, 322) He knew that to go against this light would cause her heart to become seared. And it was this that he eventually believed was happening all across England. Because their sin was now willful he would begin calling people to repentance on this matter.

Conclusion:

Let’s circle back to around to our central question. Can one professing faith in Jesus hold a theological position or engage in activity which is inconsistent with Christian redemption? I believe Newton would say, “absolutely!” Christians often hold theological positions and engage in activity inconsistent with redemption.

But the answer takes a darker turn when we ask whether or not a Christian can knowingly and willfully hold positions and engage in activity they know are inconsistent with redemption. Newton would have far more concern with the latter over the former. And I believe we should as well.

I realize this does not specifically answer the question of what to do with someone like Jonathan Edwards or George Whitefield. But I believe it adds a layer to the questions that we need to ask when assessing. And that added layer, I believe, will help us to view our own position with a bit less certainty. And maybe this way of thinking can also help us give more grace to those who are engaging in present sin or error.

—

I would also suggest reading this piece by Marty Duren